“I control the mice with a cat, but how shall I control the cat?”

- Franz Kafka

There are few things I’ve been more vocal about than my mistrust of cats. Among friends, conversationally, and with total strangers, I’ve decried their prideful nonchalance and pompous swagger. I even spoke of my hatred of them in my book, where I also criticized Cats the musical and Cats the movie, neither of which I’d seen.

It wasn’t enough to be anti-feline. I was also a proud member of the “Dogs Are Better Than Cats Club,” a canned but hefty group made up of people who are allergic, were scratched as a child, or who just can’t work out how an animal wouldn’t want to be by their side 24/7. “Dogs rule, cats drool!” a younger version of me might proclaim, in a fictional world where I say things like that. “Even though cats don’t actually drool.”

But oh, no no, mythical Olivia. Cats do drool. Real me knows this, because I’m now the proud owner of one.

Let’s rewind. Like many recovered bigots, my story starts with a betrayal. Or, more accurately, a perceived betrayal. It was the summer of 1995. Weeks before my fourth birthday, our next door neighbors’ cat, Myrna, had a litter of kittens. Myrna’s humans, Corky and Shirley, called my Mom asking if our family wanted a pet. My Dad was hesitant, as my parents’ first cat, Chaz, who had died by the 90’s, was famous for curtain climbing, Houdini-esque escape tactics, and general mayhem. Plus, Myrna was a known grump, prone to swiping at anyone who crossed her path. There was a chance her kittens would be the same. Alas, my birthday gift that year was a little black ball of fur I called Joyce.

Yes, Joyce. Joyce, because that was the name of the love interest in the film The Adventures of Milo and Otis, a 1986 live-action adventure comedy starring an orange tabby cat, Milo, and a pug, Otis. I was obsessed with it as a child. It’s been years since I watched the movie, but I’m confident, despite my hazy memory, that there’s absolutely no way it would be made today. There’s a scene where Otis fights a bear cub, and another where Milo is chucked into a wooden box and thrown off a waterfall. Reminder: live-action.

Joyce, my Joyce, was an independent spirit. Taking after her mother, she wasn’t cuddly or social. She had a strong hunter’s instinct and would chase anything resembling prey. I have memories of my brother, David, trying to pick her up and getting seriously clawed. This became a pattern over the years for me and Dave; he would do the physically or emotionally destructive thing first, pay the proverbial piper, while I cautiously watched, mentally noting what would get me into trouble, and what would keep me safe.

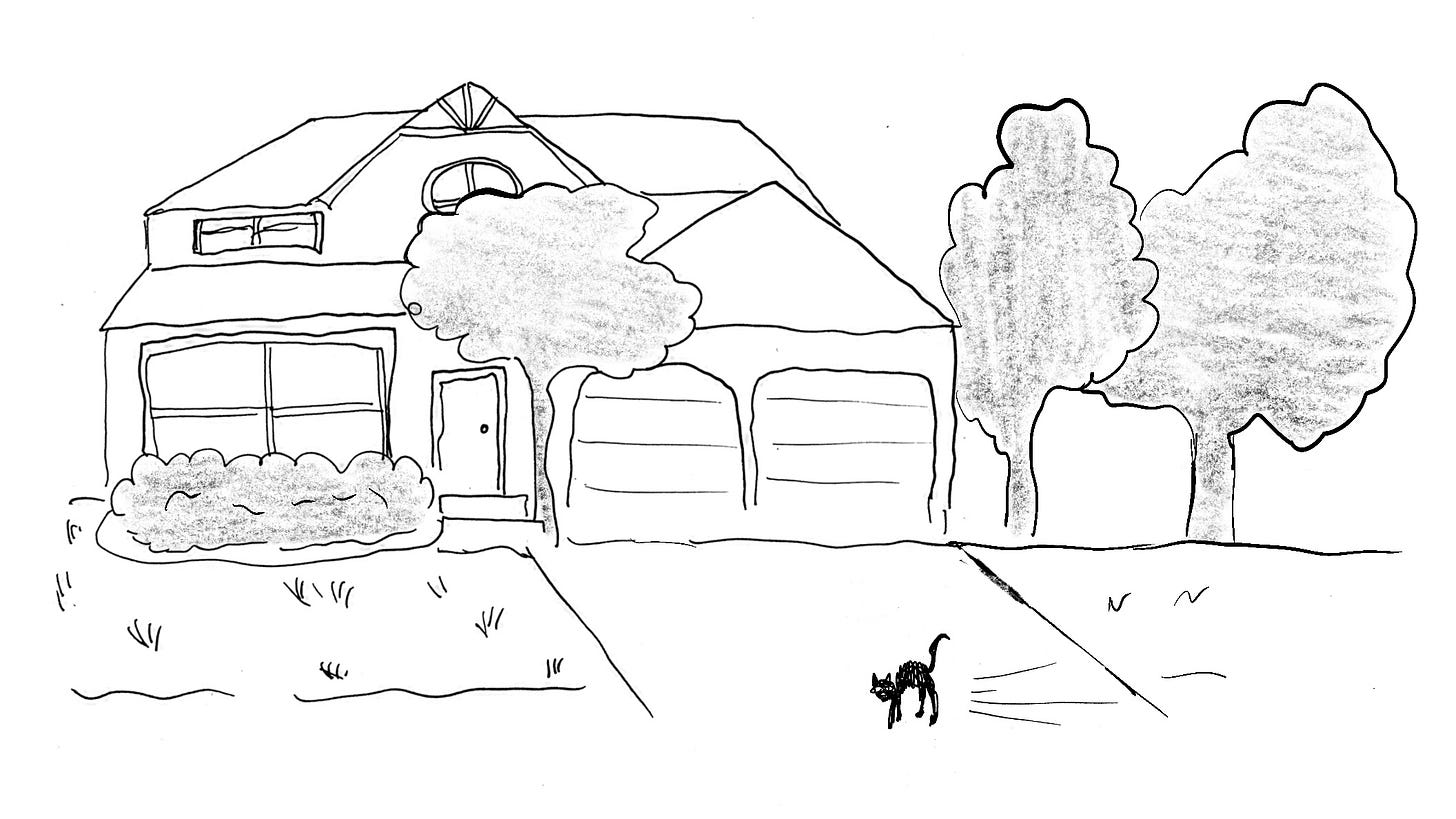

Decidedly, I avoided Joyce. She wasn’t like the cats in the movies. She didn’t purr or circle my legs. She was unpredictable. She couldn’t be tamed. And when we got our dog, Rosie, two years later, Joyce hid in the garage, refusing to come inside. We lived in a suburb of Washington state, in a calm and friendly neighborhood where cats often roamed free. Joyce became one of those indoor/outdoor cats, coming to the garage to eat and sleep, and exploring the rest of the day.

Her travels eventually brought her to our neighbors’ home, who welcomed her into their then-dogless sanctuary with food and love. Joyce was a hustler, and in our neighbors, she found a place that fulfilled her needs. And hey, she charmed them, too.

So for a time, we had a cat and a dog, but really just a dog. We’d see Joyce sauntering about the street, but she didn’t feel like ours. On the contrary, the dog was everything. Rosie, a German Shepard, was anxious and loyal and very sensitive. She loved us with an almost melancholy intensity. Unlike Joyce, she couldn’t physically separate from us. When we went out of town, she would cry and become lethargic and refuse to eat. Once, when I was blow-drying my hair, the backside of the drier sucked up my locks to the root, and I yelped, saying to Rosie: “Go get help, girl!!” Lassie-style, she rushed to my mom. Moments later, they both came to my rescue.

Joyce didn’t save things; she hunted them. She was action-oriented, predatory. She went toward everything, and this was strange to me. Conflict-avoidant from the start (flashback to me watching my brother get in trouble), cats became associated with a wildness I could never quite access. Dogs, on the other hand, were trainable and fell in line. They were love personified. Cats didn’t care.

One morning, we got a call from our neighbor, with whom Joyce was still living. There had been an accident. In pursuit of a mouse, Joyce had attempted to shimmy under a fence. Relentless, gritty gal that she was, she succeeded in killing the mouse, which they found clenched in her paw. But her body was wedged so tightly, that our neighbor had to take the fence off its hinges. When removing it, the whole thing fell on her hindquarters. In the vet’s office, we were told that she was paralyzed from the waist down.

There was a small chance Joyce would walk again. Small, but possible. My mom, relentless, gritty gal that SHE was (and is), heard “possible” and said she’d try. We took Joyce home and for months, she lived in my parent’s bathroom, where my Mom guided her through daily physical therapy. (Imagine a cat on its back while a human holds her little legs and rotates them, bicycle-style.)

A nature girlie forever, Joyce pined for the outdoors. Every other day, my brother and I would take turns sitting with her in the front yard, as she watched the squirrels she once chased scamper by, the clouds she once pranced with in unison dissolve in the wind.

A few weeks into rehab, the door to my parent’s bathroom was mistakenly left ajar. Rosie had entered Joyce’s sick-room. Sound the alarms. When I say that these two animals hated each other, I mean blood-spitting, vitriolic, unhinged hate. In their younger days, Joyce would swat at Rosie, and Rosie would back Joyce into a corner, threatening to bite. But that day, the two of them were practically nose to nose and did nothing but stare, bewildered, into each others’ eyes.

Months went by. Mom didn’t give up. Every day it was bicycles, bicycles, bicycles. I suspected Joyce was humiliated by the whole thing. She’d never needed anyone, and now there she was, being carried around like a baby.

But then, one day, a miracle. Joyce slowly moved her back legs. First it was just motioning toward the litter box. Then, it was actually getting into the litter box. Eventually, she could walk again.

I still remember the day she jumped on the bathroom counter. She acted as if nothing had ever happened.

And the first thing she did with her second chance at life? She went straight back to our neighbor’s house.

Dad was furious. “After all you did for that cat?!” he said to Mom. But Mom never resented Joyce. I guess that’s true love. Stay or go, I cherish you still.

I resented Joyce. I wished she’d stayed. For a moment, when she was home with us, it was like she was our cat again. But I also knew she wasn’t herself. Now, I think that Joyce was what writer Clarissa Pinkola Estés calls a “Mistaken Zygote.” A little soul that was truly meant for a house a couple doors down. She couldn’t be ours and be who she really was at the same time.

But in my child’s eyes, Rosie was the hero and Joyce was the villain. To Rosie, I told my secrets. To her, I sang. I had this feeling that she really understood me. But that’s just the thing— most dogs live for others. Most cats live for themselves. And for years, I thought that was selfish. Not so much, anymore. I learned just as much from my cat, as I did my dog. Animals don’t just teach you to love, they also teach you boundaries.

We had some wonderful years with Rosie. Then, when she was seven, she was diagnosed with a brain tumor. My only other experience with a sick animal was Joyce, who defied the odds and got better. Even though they were opposites in so many ways, I thought, in this regard, they’d be the same.

The day we put Rosie down, my grandparents, who would often watch her when we were away, came over to be with me and my brother. Her condition caused her to bleed from her nose, which was difficult to see at thirteen, let alone any age. I hid in my room until my grandma knocked on the door and gently suggested I spend a moment with Rose before she left. I am so grateful for that. I remember sitting with her and looking into her soft, tired eyes. Repeating “I love you, I love you, I love you. Thank you, thank you, thank you,” until it was time to go.

After Rosie died, Joyce started cautiously coming back to the house. Just the driveway at first. Then, the front steps. Finally, the doormat. Somehow, she knew that the dog she disliked was out of the picture.

We are prone to assigning human emotions to pets. I’ve done it this entire essay. But the way Joyce behaved was all animal. This was no longer Rosie’s territory. She was safe. She left dead mice, as gifts, on our porch. Suddenly, she would let my Mom pet her. At the time, I found these gestures insulting. But Mom? She always opened the door. Joyce even came inside the house occasionally. She’d slink around for a while, then leave out the back, hopping fences until she was home.

Maybe, with the mice, she was saying sorry. Maybe she was saying thank you. Maybe she was saying, “You want these? I can’t eat them; they’re diseased.” Either way, she circled our legs and purred, reminding us, perhaps, that there were no hard feelings.

When Joyce died, after a long and lusty life, we were given half of her ashes.

A cat’s love must be earned. Interestingly, my love for cats has evolved the same way. Slowly, with small deposits over time. I don’t think I’d even call it love, exactly. More of an appreciation. I started to warm up to my partner’s cat, a big, fluffy tough-but-soft Maine Coon named Sonny. One morning, he slept on my stomach. That was the tipping point. He got me.

So, for my birthday this year, I adopted a cat. Her name is Susan (Suzy, Suz, Smoosh, Snoozer, Pumpkin Face, Lil Mama, the list will inevitably go on). With her, I feel the gentle thrill of a bond still forming.

Suzy is young, only about a year old, and her life thus-far has been chaotic. She was almost euthanized at a South LA Shelter because of a neck injury. Stray Cat Alliance took her in, and performed two surgeries. Ultimately, she was diagnosed with ulcerative dermatitis, a rare, non-contagious skin condition. She’s spent most of her life in small cages, and yet, when I first met her, she immediately hopped into my lap. Then again, when I saw her a second time, she bit me.

My friends, knowing me well, got me a book of cat poems when they heard about my new pet. I like this one, by Amy Lowell, called “To Winky.” Here is a piece of it:

Cat, I am afraid of your poisonous beauty, I have seen you torturing a mouse. Yet when you lie purring in my lap I forget everything but how soft you are And it is only when I feel your claws upon my hand That I remember— Remember a puma lying in a branch above my head Years ago

Susan is both wild and sweet. She’s everything Joyce was— independent, selfish, smart, fierce— but she will also curl up in the crook of my arm, and sleep. She has an underbite. Her coat is “harlequin,” meaning she is predominantly white, with a cap of black on her head and a wash of it on her tail, like she was dropped in an inkwell. She has a tiny mustache to one side of her tiny nose, which sits in the middle of her tiny head. She will follow me into rooms, watching intensely, and when I notice her, scamper off, pretending not to care. But I know she cares. In the mornings, she looks at me, her paws making biscuits on my neck, her face pressed against my chest– big, green, otherworldly eyes shining. She’s so happy, she drools.

Olivia, it was an honor and a privilege to be a part of Joyce’s life…thank you for sharing. She was a heck of a cat!!

The Neighbors

Olivia- I loved this story for so many reasons…great honest and humorous memories of old days in the neighborhood! I remain a serious dog lover, but this gave me a glimmer of hope.😊